What Do You Remember About Rippey?

The Rippey, Iowa, Sesquicentennial will be held on Saturday, August 1, 2020. If you have personal remembrances of Rippey, you are invited and encouraged to share those memorable stories. Just send your remembrance via email and we’ll get it posted on the Rippey News Web site, as well as on Facebook sites of the Friends of Rippey and the Rippey Sesquicentennial. You write down the anecdote or story–a page or two–and we’ll do the rest. Phyllis McElheney Lepke is serving as our volunteer coordinator and stories may be sent to her at Rippey150@gmail.com.

The information for this remembrance was written by Artage Zanotti’s daughter, Gina Zanotti Daley, who is also the niece of Lester Zanotti. She researched and wrote several papers on the history of mining and her grandfather while a student at Iowa State University in the early ‘70s. Gina’s grandfather, Andrew, also known as Andy, was a community leader and strawman for the mine until his life ended in a mining accident in 1947.

Coal mining was big in the neighboring town of Angus, being the largest mining town in Iowa with 5,000 persons living there, and nine major companies mining coal. The town reached its peak in 1884. People were optimistic about the town even though it had a bad reputation for its wildness of drinking, gambling, and shootings. A strike resulted in the price of coal being raised, and eventually the major company, Climax, left. The jobs were gone, and the population dwindled. Many of the homes were moved to surrounding towns, including Rippey. The railroads moved too, and Rippey was on the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad line.

This is a long and very interesting history. Let us begin…….

Coal Mining And The Zanotti Family by Gina Zanotti Daley

In 1931 Mac Elvin was drilling a well for water when he discovered a 5 foot vein of coal at 169 feet. This was about one mile south of the current Squirrel Hollow Park. He called a coal salesman to inspect the sample. The end result was the formation of the Greene County Coal and Mining Company. The company was launched with 14 stockholders providing $68,000.00. Joseph Strachan was the major stock holder, having learned the mining business in the British Isles, prior to coming to the U.S. The coal was considered low grade bituminous with 25% ash, twice as much as in eastern coal, but it was good burning coal, and the locality made it desirable as freight costs were much less than if shipped from the East.

Andrew Zanotti traveled from Italy to America with his father in 1909 when he was 13 years old. In Italy the family had owned large amounts of property prior to WWI, but the government took the land. The plan was for Andrew to earn enough money to bring the rest of his family to America. His father returned to Italy leaving Andrew to learn mining in Missouri. He arrived in Rippey at the age of 33 in 1930. He helped to start the Greene County Coal and Mining Company. At its peak it produced 400 tons of coal per day and provided jobs for nearly 200 persons.

Work began at 8 a.m. and ended at 3:30 primarily during the coolest 9 months of the year. Each miner carried his own lunch and ate his meal in the mine. A miner could carve six tons of coal per day and receive 97 cents per ton. Nearly 100 miners worked underground. Many single miners lived in camps composed of rather poorly constructed temporary housing, but several including Andrew Zanotti, lived in Rippey. The Zanotti family would have to be described as very industrious, as well as creative. Andrew lived in Madrid at the time of the opening of the mine, and lived in Rippey the first year, commuting back to Madrid on the weekends. Upon moving to Rippey, they rented rooms to two or three borders who worked at the mine, and Andy drove them to the mines being paid on a weekly basis. He had a Model T ford which he used to travel to the mine.

In 1932 he purchased a V-8 Ford, one of two purchased in Rippey, the other one being bought by a local banker.

The mine was about one mile long and 147 feet deep. (Think the width of a football field). Once the corridors were extended three hundred feet away from each side of the main shaft, another corridor would be made at a right angle to the first. Off of these, rooms were made from which the coal was dug.

The miner’s room became longer the further in he dug, eventually nearly coming in touch with the miner working in the opposite room. Hundreds of posts had to be placed in staggered positions to prevent the slate or stone room from caving in on the miner.

Andrew laid tracks on which the coal cars traveled. He drilled the holes for the powder and fuses which were used to explode and break down the coal. The tracks extended out of each room and joined main tracks headed toward the hoist at the main shaft. Small mules were used in the mine to pull the cars to where the miners loaded them and to an area where a winch type motor pulled them to the mine shaft. The loaded cars were then hauled to the surface by an elevator type conveyance. Coal could be delivered from the mine to an individual’s home for $4.00 a ton. Sometimes as many as 50-60 trucks were in line during the day as well as the night for 24-hour loading.

Most of the coal was used in Greene County, but some was shipped by rail to northern Iowa and southern Minnesota.

The Rippey miners were not union organized, but the Madrid area miners were. Andrew learned that union leaders from Madrid were coming to organize the Rippey area miners. Had they successfully organized, the price of coal would have been raised, and because of its poor quality, the action would essentially put the mine out of business.

In anticipation, Andrew called the sheriff and told him trouble was brewing.

According to a private interview conducted by Gina Zanotti Daley, “When Andrew left for the mine that morning, he had his German Luger stuck inside his waist band. He wasn’t looking for trouble, but he was going to be ready. Andrew wasn’t one to run away from a fight. About the time he got to the mine, the sheriff also arrived. The union miners arrived from Madrid and piled from their cars. Brewing for a scrap, the sheriff fired a few rounds of ammo into the side of a nearby hill. He told the union miners to get back in their cars and never show their faces again.” They complied at that time.

Mining provided a steady employment except in the summer. To supplement his income, some summers Andrew worked for local farmers, and one summer he and his family went to live in Chicago, where he worked as a yard man.

To keep water from building up in the mine, from the springs coming into the mine, water was pumped to the surface through pipes that were located against the side of the mine shaft. Mr. Strachan (the owner) and Andrew were replacing some of those water pipes in the shaft one Sunday morning. They were using the top of the elevator as scaffolding, and the pipes propped on the surface with lumber and jacks. As they were going down one elevator, the other elevator was coming up. It hit some of the lumber or jacks and knocked them over and the elevator plunged killing the two men. Andrew was 51 years of age; Joseph Strachan was 61. This occurred in 1947.

The miners were not a separate community. Artage did not feel he was ever discriminated against because of being Italian or a coal miner’s son. After his father was killed, the community stood behind Mrs. Zanotti and her two sons. She was provided a job in the bank, and whenever Artage or Lester needed summer work, someone always offered a job.

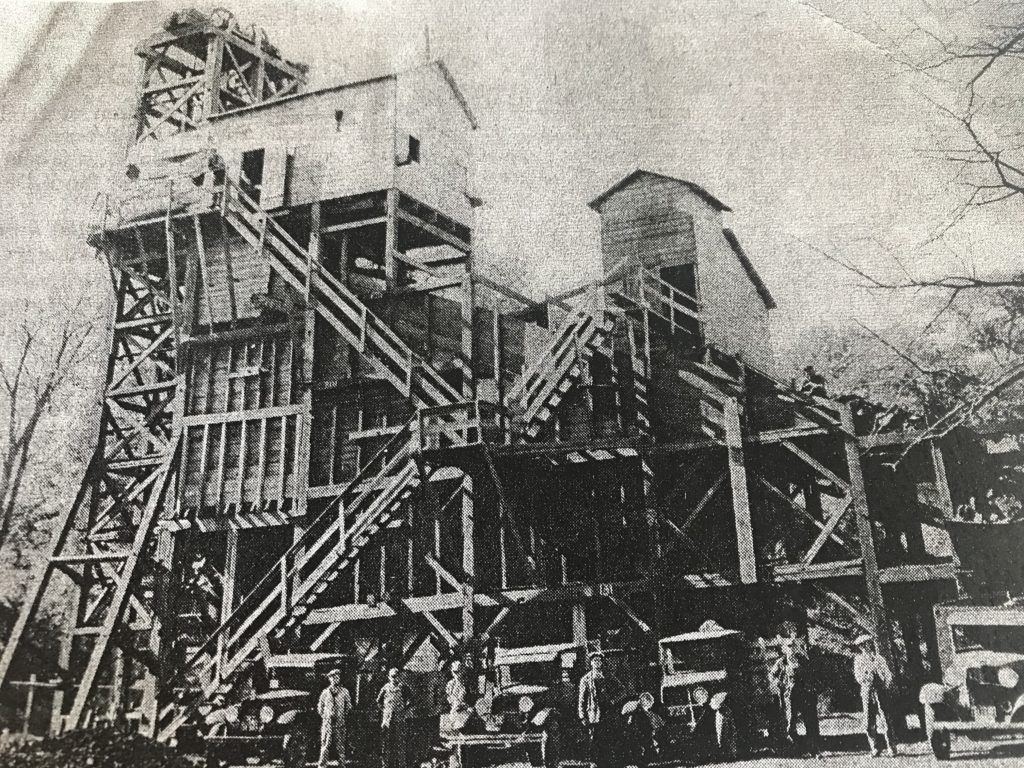

Later that year the tipple (top of mining construction) burned. Gas was beginning to rival coal and the mine subsequently closed in 1948.